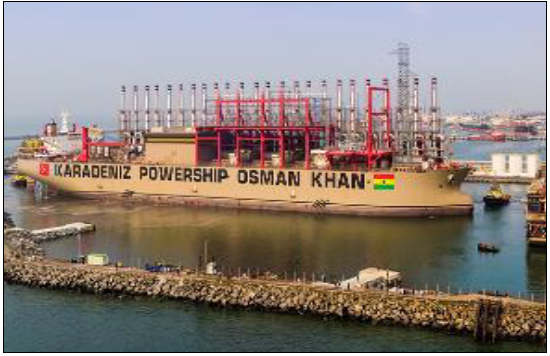

A project to quickly ease South Africa’s electricity supply constraints by using floating powerships has come under fire by energy analysts, who have questioned why agreements will lock SA into using the ships until 2042.

Earlier this month Minister of Energy Gwede Mantashe announced the names of the eight preferred bidders for SA’s “Risk Mitigation IPP Procurement Programme” – an initiative to fast-track new power production to cut down on load shedding and save on diesel costs.

The bulk of the 1 845 MW in new energy capacity will be provided by Karpowership, a subsidiary of Turkey’s Karadeniz Energy Group.

Karpowership operates the world’s largest fleet of “fully self-contained floating power stations”, which can quickly be sailed to new ports and connected to a country’s grid.

“Powerships will contribute to the avoidance of load shedding during peak periods and when unplanned breakdowns occur at other power plants in the system,” it said in a statement.

But three energy analysts told Fin24 that the length of the power purchase agreement that SA was entering into with the powerships was too long.

“No-one has ever signed a 20-year contract for powerships. They offer a short-term emergency power option when there are no alternatives,” said UCT Professor Anton Eberhard, who also chaired the Eskom Sustainability Task Team. “There is no room for negotiation of its terms now otherwise losing bidders will mount a legal challenge arguing the process was not fair for all participants.”

The Department of Energy justified the length of the contracts by saying they were necessary to keep costs down, given that new infrastructure would have to be built.

“It must be understood here that the need for long-term tenure is to ensure lower unit cost by amortising [gradually writing off the initial cost of an asset] the capital cost over a period of time,” the department told Fin24. “This is the same basis applied to ensure lower unit cost from (the) renewable energy independent power producer programme. The department said the process was, “… open for anyone to bid their best projects.

“The outcome is therefore based on best projects out of the 28 bids received by the Department.”

FLOATING POWER STATIONS

The powerships will be moored at the ports of Coega, Richards Bay, and Saldanha Bay, where they will provide a combined total of up to 1 220 MW of ship-to-shore electricity made using liquified natural gas, likely sourced from Mozambican gas fields.

The other preferred bidders are offering a mix of solar, wind, and gas power, as well as battery storage. The government says it will start connecting this new power to the grid by August of 2022.

Speaking to Fin24 on Thursday, Hilton Trollip, research fellow in the Global Risk Governance Programme at the University of Cape Town, said that if the ships had been leased for, say three, years, they would provide “good value”.

Under this scenario, the ships would be able to help fill SA’s energy gap – the difference between what SA’s ageing fleet of coal power stations produce and demand – while new permanent power plants were constructed. Power produced by the ships would, initially, also help reduce load shedding, which continues to severely impact SA’s economy.

Energy would likely be sufficient to allow SA to spend less on expensive and dirty diesel, which is currently used extensively at peaking power plants to cut down on load shedding.

SA could, during these three years, build wind and power energy and onshore gas plants, argued Trollip.

“If you want to build a gas turbine onshore, you can have it working in two years from the date you signed the contract. “At that time we would say thanks very much Karpower”.

But the agreement locks SA in to using the ships for 20 years – far longer than they would be needed under an “emergency” or “stopgap” scenario.

For Trollip this raises the question – why not just lease the ship for three years, and – during that time – build SA’s own on-shore closed cycle gas turbines?

Professor Sampson Mamphweli, director of Stellenbosch University’s Centre for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies, also questioned the length of the contracts.

“The ships were not supposed to be given a PPA [power purchase agreement] that goes beyond five years because they will be producing expensive electricity, and that price is for emergency procurement, which is supposed to be a short-term price,” he said.

Costing the ships

According to an estimate prepared by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, the powerships would cost SA between R160 billion and R218 billion over their 20-year lifespan.

At the media briefing earlier in the month, Mantashe did not give an estimate of what the power ships would cost in total, beyond sharing their evaluation price, which has a weighted average of around R1 536 per megawatt hour.

Mantashe said the eight preferred bidders are required to reach financial close by no later than the end of July 2021.

“All South Africans can hope for now is that the Powerships will not be able to achieve all the necessary environmental consents and port approvals by the target financial close date in July, in which case the DMRE could cancel the tender award,” said Eberhard.

Three draft environmental impact assessments for the three ports, published at the end of February, have proposed that the powership projects should be given the go ahead.

Once all feedback from the public has been included, the reports will be submitted to the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF), who will then have to make a decision to either grant or refuse environmental authorisation for the ships.

In addition to the key environmental authorisation, the projects will need to receive an atmospheric emissions license – also from the DEFF, as well as a water use license from the Department of Human Settlements.